Grief is the price we pay for love.

Most people won’t remember what they were doing on Dec. 30, 2007. Cindy Larson-Casselton vividly remembers that date as the day her husband, Rusty Casselton, died. Now three years later, the funeral is over, the meals are no longer being delivered, and people have moved on, while Cindy is still dealing with the grief and, simultaneously, the awkwardness of navigating this new territory alone.

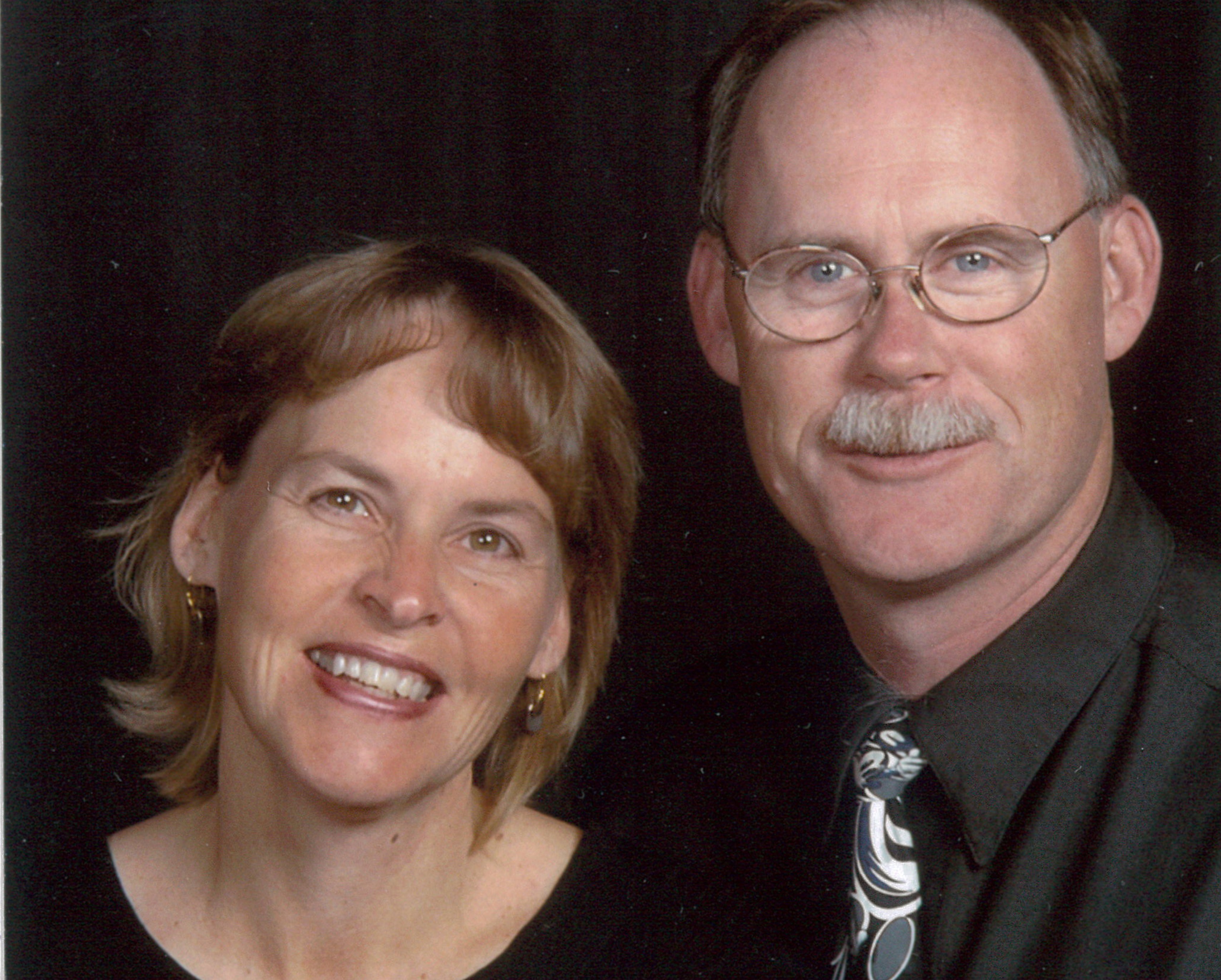

Rusty was chair of the film department at Minnesota State University Moorhead. During his short time there, he developed the film major and was known all around the world for his efforts in film restoration and preservation.

Cindy is an associate professor in the communication studies and theatre art department at Concordia. She teaches speech and communications classes. But sometimes, even the most carefully chosen words are inadequate.

Back in 2007, Rusty Casselton wasn’t feeling very well. He went to see his doctor several times.

“Every time we went in,” Cindy explains, “he’d be treated for [his] heart…because there’s a bit of a history in his family. And you know, I could tell. He wasn’t on his game. He just never really felt good.”

The doctors decided to remove his gallbladder—after an ultrasound showed it to be unhealthy—and he and Cindy thought that was going to solve his problems.

“I’m feeling pretty cocky that morning because I had the day off [and] it was outpatient. Three little cuts, remove the gallbladder. He was even going back to work that same day because that’s how he is,” Cindy remembers, smiling briefly. She leans back into her office chair, calm and reflective. On the floor beside this petite lady’s chair are two boxed film reels, both with Rusty’s name in the return address.

She was in the outpatient waiting room, drinking coffee and grading exams, when she realized it was taking longer than they’d told her. She asked the nurse, who went to check.

“When she returned, she said, ‘Mrs. Casselton, we need you to come with us,’ and they put me in a small room and the surgeon comes in and I knew immediately something was wrong. He had pictures in his hand (of cancers in Rusty’s liver and surrounding areas) and he doesn’t give me any eye contact. And I remember [him] saying, ‘I am so sorry. There’s nothing we can do. There’s nothing that can be done for this.’ “

Rusty had what was called carcinoid tumors.

“So here’s the two of us, we just get this news, you’re husband’s going to die. Your life has just changed,” Cindy says, “and I took him back to work that day like he wanted. And Monday he gets up and goes back to work and we keep going.”

Rusty and Cindy’s two daughters, Hannah and Amanda, were both in high school at the time. Hannah was a junior, Amanda was a freshman. When they learned of their father’s diagnosis, they immediately began to do their own research. They couldn’t imagine why their dad couldn’t at least have chemo.

The Casseltons drove to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester for a second opinion. The oncologist confirmed the original diagnosis. Rusty had two-to-five years left, but there was a procedure that would prolong his life.

“That at least gave us some promise and hope,” Cindy says.

“We turned those into our grand moments.”

Rusty and Cindy began to make regular trips down to the Mayo Clinic.

“Probably the best times Rusty and I had, at the end, were those trips back and forth, just the two of us,” Cindy recalls. “We’d always stay in this little flea-bitten hotel—which became very charming to the two of us—so we could spend a little more money on a good meal.”

Rusty fought hard against the cancer.

“He’s got two daughters in high school; we’re months away from our twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, for which he had grand plans. He had everything to live for. And he was building a beautiful program at MSUM,” Cindy says.

It was difficult, Cindy remembers, trying to balance classes, go to Mayo, and keep it all secret. They told a few people, and had a support system in place to step in with the girls in an emergency.

“[But] the secrecy thing, people have trouble with. And it wasn’t to keep a secret, it’s because Rusty didn’t want people looking at him, wondering when he was going to die. He’s a very private person. And it was his to tell, not mine, so I respected that all along.”

Other people, however, did not. They told her, “Well, if we would’ve known, we would have been praying for you.” She remembers thinking, “I would hope you would be praying for me anyway.” Her eyes grow soft again and she melts into her chair as she admits that she can understand their shock, too, and that she doesn’t blame them for what they did or said.

She points to his picture on the wall, one of many. “He had cancer then,” she says. The picture is of Rusty and a friend, standing side-by-side and smiling. Rusty looks happy and healthy with a head full of red hair. He began to get thinner but, as Cindy says, “People just thought he was losing some weight. He actually started looking better than he’d looked for quite a while. His color stayed good. He never once complained [or] changed much in terms of what he did and was capable of doing. His students didn’t know. The first they knew was when he died.”

It didn’t bother Dawn Duncan, professor in the English department—who has been a close friend of the Casselton family both before and after Rusty’s death—that she wasn’t told about Rusty’s cancer before he died.

“That’s their business,” she says. “When a person is going through that sort of thing, it’s up to them what they want to say and do, to be able to live out the rest of their lives in the way that’s most meaningful to them.”

“We know there’s going to be some pain.”

In December, Rusty went to the emergency room, swollen from the waist down. He was sent to Mayo where his oncologist told him it was time to do the liver procedure.

“And Rusty says, ‘Can it wait? I want to go back and see my daughter dance,’ because Hannah’s dream was to dance [the role of] Clara in the ‘Nutcracker.’ … So he does. He comes back and watches her dance this beautiful dance. And she has no idea what’s going on,” Cindy recalls.

The procedure was scheduled for Dec. 28. “We knew both of us would be on break. So we journey down there. We have our computers. We have our books. We’re both going to write our course guides. We know he’s going in the hospital for a week. And we know there’s going to be some pain. But we’re both very positive.”

On the trip down they discuss the risks, but Rusty’s sure he wants to try it out.

“For the first time…he tells me where he wants to be buried. Up to this point we’d never even talked, ever, about the possibility of him dying. And he wants to be buried, believe it or not, at the little country church where we were married; where my parents live maybe a half-a-mile away. And I would have never, ever, guessed that one. And why we talk about that I don’t know. But we do.

“We meet with the surgeon. The surgeon is cocky as heck and I like that. You want your surgeon cocky. He’s like, ‘No problem, Rusty, we’ve done a million of these.’ And we’re like, ‘Great!’”

After the procedure the surgeon tells Cindy that it couldn’t have gone better. He even tells her that instead of having to do this in three sessions, it went so well that they’ll probably only have to do one more.

“And then I go and sit with him while he’s waking up,” she said. “He’s in a lot of pain. A lot of pain. We both knew that was probably going to happen, but it [seemed worse]. They were having trouble controlling it.”

On Saturday things began to fall apart. Rusty’s kidneys start to shut down, and with Cindy’s permission, they start him on dialysis.

It’s the wee hours of the morning and Rusty is responding well to the dialysis when Cindy is told that it’s okay for her to go for a little while. She heads back to the hotel to take a shower and at 5 a.m., while she’s drying her hair, she gets a call saying she needs to get back. He’s coded [his heart has stopped].

“I come back and he can’t speak to me ever again. He’s got a breathing tube. He can speak to me in other ways, though. He’s awake. They brought him back. But then, it’s the conversations of, ‘This is it,’ [with the doctors].”

Meanwhile, Rusty’s veins are collapsing and his brain begins to swell. He codes two more times and they bring him back each time. They try to find a vein for his IVs, and end up having to try to go through the carotid arteries in his neck. They even ask her to hold his hands down because he’s fighting them, while at the same time he’s begging her with his eyes to make them stop.

And the doctor finally pulls Cindy aside and tells her that she’s should decide how many times they’re going to keep bringing him back because his organs are shutting down.

“I had the peace that surpasses all understanding…”

After Hannah and Amanda have a few moments with their father, Cindy acknowledges that it’s only a matter of time before his heart will stop again, and she makes the decision to stop resuscitating him when that happens. She has them turn the sounds off on all the machines, and then she climbs up into the bed beside him. “And he’s holding me, I’m not holding him. He’s holding me when he dies. And I sit there and all of a sudden I had the peace that surpasses all understanding overwhelm my heart and I looked up at him and he was gone.”

“It’s a part of who I am…”

Rusty died just two days after the procedure that was supposed to extend his life and only nine months after they’d found out he had cancer.

They don’t know, to this day, what went wrong. “There was no answer,” Cindy says. “I’ve had to learn to live with the questions, and that’s really become stronger every day for me. What does this mean? There’s no explanation anyone can give.”

Cindy and the girls had barely arrived home when people started coming over. Dawn Duncan was one of those people who came to offer whatever help she could.

“Even if the person who’s grieving is not in a place where they can talk to you, or be with you, there are things that need to be done, and somebody needs to do them. And so, that was just my first instinct,” Dawn says.

“That’s a wonderful tradition,” Cindy says. “I’ve done that for a lot of people, but never thought much about the importance of it. People were so kind to organize the meals and stuff.”

There was a lot of shock. “People didn’t know what to do or say. I didn’t know what to do or say,” Cindy admits. She didn’t know what to ask for or what she needed. She just knew she had to keep going and that they’d be okay.

“I think we handle people with too much caution [when they’re grieving],” Cindy says. People would ask other people about her instead of coming to her directly. But she really needed that contact and missed it. “You reach that point where you feel like nobody cares for you anymore, and I don’t know why I felt—and feel—that way.

“I think people, for a long time, were waiting for us all to fall apart. Then they would come. But we didn’t. That doesn’t mean inside that I’m not a mess. It’s not easy. But I try not to bring it with me to work, because my students don’t deserve that, nor do my colleagues. It’s a part of who I am and there’s a balance there, but I’m not sure what that is.”

“His presence in our home is everywhere.”

Cindy thinks the hardest part now is the transition from being a couple to being single. People don’t know what to do with her. The Concordia banquets are tough.

“No one thinks about how hard that is to show up by yourself now,” Cindy says. “And at tables for eight, what do I do? Or everyone’s meeting at this establishment, and I’m not walking into a bar by myself at this point in my life. I’m not going to do that. And in my case, I don’t know how to ask for help, so I don’t. That doesn’t mean I don’t need it. So it’s people, like Dawn Duncan, who can—because of who they are—simply do things or encourage or make things happen with that in mind. And Cindy Carver who knows there’s nothing like having a meal with someone else and so hardly a week goes by that we won’t have a meal together.”

It’s been three lonely years since Rusty’s death. “I am so tired,” Cindy admits. “I haven’t had a good night’s rest since he died. I haven’t slept in our bed since he died. I sleep on the couch. You can’t think. I fall asleep fast, but then I wake up and I’m up all night. Nighttime’s scary. The aloneness. But I can be alone in a room full of people.”

Cindy treasures those last six months especially. “But I lost my best friend. And I don’t know how to go on, I really don’t. The key for the girls and I has been to get up every morning. And thankfully the girls—I know they could have responded in many ways—have just been wonderful. We talk a lot about him. His toothbrush is still in the bathroom. His bathrobe is still hanging up. His presence in our home is everywhere. And we’re okay with that.”

“The biggest thing I’ve lost is confidence…”

There are so many things Cindy misses about Rusty. She misses his silly stories. His sarcastic humor. She misses his help with the smaller things—like stirring the rice crispy bars on the stove when the mixture gets too thick for her to stir by herself—and with the bigger things—like when her daughter needed a good used car this past summer. Cindy and Hannah did all their homework, researching makes and models, comparing prices, etc, before buying the car.

“On the way home we both realize we never once looked at the engine. I never popped the hood on it. It never occurred to me. We bought a vehicle and I’d never once looked inside the hood. We get it home, and [Hannah’s] boyfriend and his dad came over and what’s the first thing they do? They popped the hood.”

She smiles as she relates this story, but you can tell she’s still irritated with herself.

“The biggest thing I’ve lost is confidence—to just live,” Cindy says. She keeps going every day because she knows her daughters need her, and Rusty would want her to, but it’s far from easy.

There are two quotes that Cindy reads every day. She doesn’t know who wrote them. The first sentence in this piece is one of them. So is the last sentence.

Courage is the strength to act wisely when we are most afraid.

I studied under Rusty at MSUM. In 2005, he changed my life forever in one moment by forcing me to become an adult and start taking my work and passion seriously. I am forever in his debt. Thank you for this beautifully written article.

Cindy; I went to school with Rusty. I replaced Rusty in Ted Larson’s office when he left MSU. We lost touch, and I wrote to him in early 2008 and never received an answer, and now I know why. Your story is touching, and I cannot begin to know your grief. My condolences for your loss.

Victoria