Always intersecting

An aspect of environmental sustainability that people often overlook is the link between environmental sustainability and issues relating to basic human rights. A general set of basic human rights can be found in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), a document that has served as a fundamental guide to international relations since World War II. In Article 25, Section 1 of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a clear link connects environmental sustainability and basic human rights by ensuring the following: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.”

When one considers that nearly half the global population lives in poverty, Article 25, Section 1 looks much more difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. People who live in poverty often live in areas with the worst environmental conditions; environmental diseases are likely to affect the impoverished because they are more exposed to environmental disease (usually due to where they live) and have lower resistance to infection. Environmental diseases are illnesses and conditions arising from manmade environmental problems. According to the World Health Organization, a lack of access to clean water and sanitation and indoor air pollution are some of the principal risk factors for illness or death. These factors primarily affect women and children from impoverished families in developing countries.

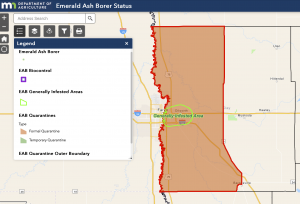

Given that over 3 billion people in developing countries still use solid fuels to cook and perform daily household tasks, it is critical to evaluate other environmental factors, such as the places where the impoverished live. In some situations, urban neighborhoods are close to coal-burning factories, which seriously compromise air quality. As a result of poor air quality, it can be difficult to find healthy food, clean water or sanitation because air quality affects all these factors. Other situations include people who live in smaller poor communities, which do not have the resources to adapt to environmental changes or environmental strife and depend on climate-sensitive resources (such as food and water). Unsurprisingly, impoverished people pay for the environmental wrongdoings of developed countries, such as the United States. The inequity of responsibility for the planet’s large carbon footprint will become more apparent if climate change continues to influence the peoples’ lives in increasingly extreme ways.

In order for developing countries and urban slums to evolve from poverty (if that is indeed a realistic or possible solution), living sustainably and working to maintain healthy environmental quality are prerequisites. I write this because upon looking at the 2015 Millennium Development Goals, I realized each one of them require a certain level of environmental quality to even be feasible to tackle (save for “ensure environmental sustainability,” which is redundant).

Attempting to tackle the general lack of basic human environmental rights among the world’s impoverished is not only a daunting task, but also a challenging one. There are many facets to this issue, and it is difficult to know where to start. A logical step toward figuring out where to start is to learn more about the issue. If the majority of people are sufficiently educated on this matter, making amendments to current actions will be easier. However, we have many changes to make to ensure this education happens in time, or that it sufficiently alarms enough people to influence lasting change. It can be challenging to understand the broader impact one’s actions have on others who are impoverished when the issue is depicted in figures on paper or on the Internet rather than as depicted through legitimate experiences. It is our responsibility to engage the world and ourselves in this pressing matter.

Be First to Comment