Carl Bailey, former professor of physics, dean of the college and author of Concordia’s mission statement passed away last Saturday at age 94 from terminal cancer.

Baily served as faculty at Concordia for 41 years. When he first arrived, the physics department had only one other professor. Bailey hired staff and expanded the department. He also worked to get some equipment for the department, including a hypervelocity dust accelerator from NASA.

Outside of the department, Bailey was also known to teach courses in philosophy. Gregg Muilenburg of the philosophy department shared more about his experiences with Bailey.

“He was a very private guy,” Muilenburg said. “He had his own accelerator over there [in the physics department] and he didn’t like to leave it.”

Muilenburg also described Bailey as “quite a reflective man who took his moral obligations very seriously.” This included the repercussions of the Manhattan project, which Bailey worked on during his time as an undergraduate student at the University of Minnesota.

“’I seek forgiveness,’” Muilenburg quoted Bailey as saying in response to his work on the project.

Muilenburg also said that he and Bailey would argue on occasion about the philosophy of sciences.

“It always made him nervous when philosophers messed with science,” Muilenburg said.

During his time at Concordia he was promoted to dean of the college, which, at the time, was a new position. He served as dean for 17 years, from 1954 to 1971.

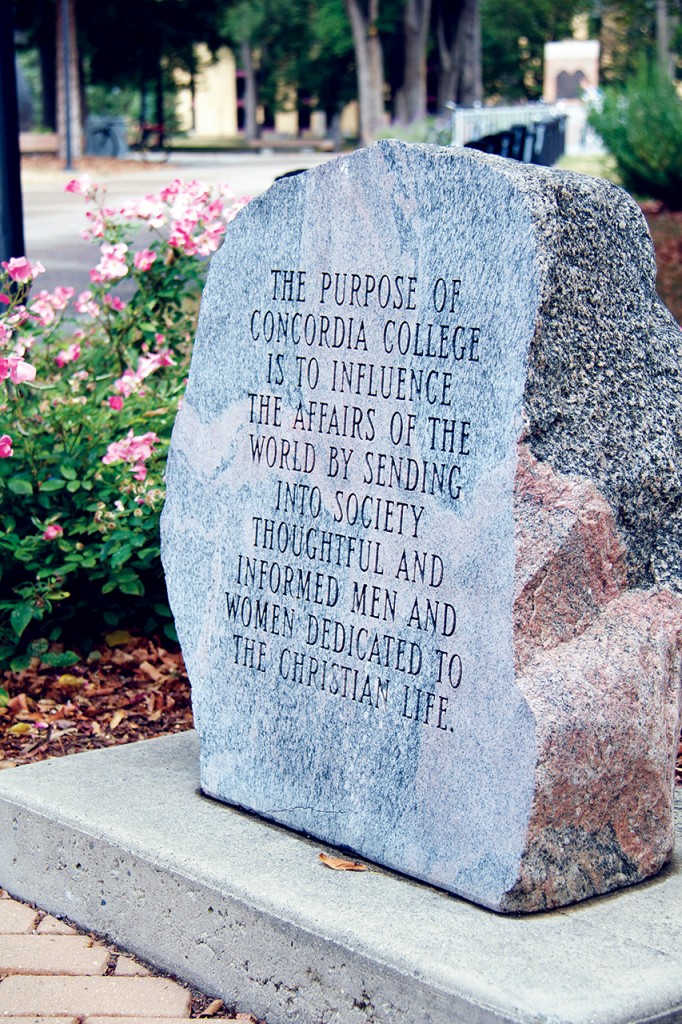

It was during Bailey’s period as dean that the Concordia mission statement was developed. This is the same mission statement that still represents Concordia.

Mark Krejci, current provost and dean of the college, explained the importance of the mission statement.

“That mission is not just something on a rock, it’s something that’s guided Concordia,” said Krejci.

Indeed, the mission statement was vital in the creation of both the Blueprint academic plan in 1991 and in BREW in more recent years, according to Krejci. The statement has been interpreted and re-interpreted in order to meet the changing needs of the college and the changing environment we live in.

Krejci explained the process: “[We ask] ‘how do we reinterpret the mission in the light of our time?’”

Bailey was also present at the college through some of the most difficult times, including during the controversy of the Vietnam War. As Muilenburg put it, “he outlived a lot of presidents.”

Throughout all this time, Bailey was well-respected amongst all of his peers.

“If he had any enemies, I didn’t know of them,” said Muilenburg.

Many professors recounted that they were well-treated when they went to speak with Bailey.

“You could go in and disagree, but you knew that he listened,” said Krejci.

Bryan Luther, current chair of the physics department, gave more insight on Bailey’s contributions to both staff and students.

“One of the great things about Carl for me was that he always had time to talk to students, to listen to you talk about your research, to talk about anything. He was just fascinated by people and by the things that they did,” said Luther.

Bailey continued this tradition long after his retirement. He would return to speak with students or staff or just come back to watch games or concerts. Mark Gealy, a professor in the physics department, described Bailey’s visits.

“He would come in and tinker around the lab, he would fix things, he would make things. That was just what he did,” explained Gealy.

Before Concordia switched to using printed backdrops for the Christmas Concert, Bailey and his wife June, would come in each year to help hand-paint the murals. Krejci described it as a massive paint by numbers. When Concordia did switch to printed murals, Krejci recounted Bailey as saying that he was going to miss painting them by hand.

“Even up ‘til a year or so ago, Carl was still coming into Concordia,” Luther said.

Bailey had started his career at Concordia as a student, graduating in 1940 with degrees in math and physics. He then left and pursued his doctorate at the University of Minnesota. Bailey’s work there with the Manhattan project was the subject of his doctoral thesis.

Gealy explains more: “At the time he finished his Ph.D. his work was too secret for anyone to read, and so these super, big-shot, household named physics guys… signed a letter to the University of Minnesota that said ‘you should give this guy his Ph.D, we can’t tell you what he did.’”